Author Archives: ruizcor

Protected: GWW 2025 Adventures V

Protected: GWW 2025 Adventures VIII

Protected: GWW 2025 Adventures VII

Protected: GWW 2025 Adventures VI

Protected: GWW 2025 Adventures I

Thank you for a great 2024 GWW Friends

Without a doubt, 2024 was an exciting year

⟿⟿⟿ Sometimes I feel like a one-man band, with no musical instruments. ⇜⇜⇜

Almost halfway into 2024, in the second half of May, GWW friends gathered in Peru. The morning of May 21, GWW-Mexico representative Arlette Fuentes met Sergio in Lima and flew together to Cuzco to start a series of activities with Peruvian environmental vigilantes and monitors. While in Cuzco, Arlette and Sergio led a community-based water monitoring session as part of the “School of Environmental Monitors, Pachamama Amachayta Awasun (Weaving Protection for Mother Earth)”. This school involves multiple events that have the purpose of strengthening capacities of female community members of Cusco and Apurímac. They gather to share and receive theoretical and practical modules related to community-based environmental monitoring and surveillance. It is remarkable to witness that locals from the native communities possess an unsurmountable ancestral knowledge about their territory and their communities, while describing what they know or have seen, unfolding every detail of almost everything within their territories. Furthermore, it is important to strengthen the capabilities of the population, especially women who stay in the territories and guarantee food for families despite any adversity they may encounter.

School of Environmental Monitors, Pachamama Amachayta Awasun (Weaving Protection for Mother Earth) in Cuzco, Peru.

==========

Two days after Cuzco our team traveled to Espinar, a town at about 3,900 meters (13,000 feet) above sea level, to conduct bacteriological monitoring, water chemistry monitoring, and biomonitoring certifications for locals. Local community members have committed to becoming environmental monitors and keep track of the well-being of the environment, as well as the dissemination of results from their water monitoring. For the last forty years they have lived with mining activities and their consequences; therefore, they promote dialogue among local actors to keep peace in their territories, and the need for the implementation of more environmentally friendly mining activities.

==========

Community members becoming environmental monitors in Espinar, Apurimac, Peru.

==========

Next stop was in the Puno region where the GWW team conducted certifications and recertifications, in all three types of GWW water monitoring for students and other volunteers, in the town of Coata. The next day, GWW-Chile representatives joined the gathering, as well as representatives from a Bolivian organization interested in implementing GWW water monitoring in their country. The larger GWW team traveled to the city of Chucuito where from May 29 to 31, in a scenario marked by the climate crisis and socio-environmental tensions, the V National Meeting of Environmental Vigilantes and Monitors was held. At this event, representatives from Puno, Cusco, Apurímac, Cajamarca, La Libertad, Ayacucho and Lima provinces gathered to reflect and encourage action in the face of the current environmental and political challenges.

Community members becoming environmental monitors in Coata, Puno, Peru.

With the slogan “our water and our lives have more value than minerals”, the meeting started on May 29 with an analysis of the current situation of community environmental surveillance and monitoring, highlighting the imposition of the energy transition based on the looting of the Global South countries. This translates into a negative impact on health and territories, due to extractive activities that do not respect human rights or the rights of Mother Earth.

Learning and sharing about local watersheds in Chucuito, Puno, Peru.

==========

October of 2024 saw our return to Chile to continue supporting the GWW expansion to more regions in the country. From north to south, Chile extends 4,270 km (2,653 mi) but is only about 350 km (217 mi) at its widest point, and averages just 177 km (110 mi) east to west. We visited again Laja, where a dozen students, a teacher and several community members, certified last year as GWW monitors, have been monitoring at three locations in Laja. They all got reunited again at this local school to attend recertification. Chilean GWW trainers Débora, Esteban, and Oscar traveled with me to conduct a classroom session with questions and answers about the three types of water monitoring that GWW promotes.

After Laja, we traveled to Tomé, the city where GWW-Chile has been holding many training sessions and other environmental education activities. The Municipality of Tomé has been a model collaborator and sponsor of GWW trainings; from the first certification training in 2022 GWW-Chile 2022, to the GWW-Chile 2023 when municipality employees and local teachers completed certifications in water monitoring. On Sunday, October 13, 2024 about 30 more monitors from other locations in Chile joined the gathering in what was considered the first annual meeting of GWW-Chile, attended by almost 90 participants. There were social activities, speeches, delicious food and sharing of numerous water monitoring stories. While in Chile, GWW also participated in the IV Meeting of Protected Areas and Gateway Communities, which are all those localities, physically or culturally, close to a protected area. Today about one third of Chile’s surface is protected under some form of land and/or marine protection. About 200 attendees participated in the event held at La Moneda Palace, a historical building that houses the president of the Republic of Chile and other ministries.

—–

By the end of 2024 GWW also had gone through sad times with the loss of Ms. Blanca Nava on May 20. She was a strong GWW collaborator from Mexico who promoted and pioneered environmental education for children with special needs.

GWW collaborator Blanca Nava Bustos from Veracruz, Mexico.

Few days later, on June 10th, Col. (Ret.) Richard (Dick) Bronson, passed away in Montgomery. He founded Lake Watch of Lake Martin in 1989 with the goal of protecting the lake’s water quality for future generations. Dick was an active monitor with AWW from 1993 through 2016, submitting more than 300 water chemistry data records. He was also engaged with the Global Water Watch Program; as the Bronson’s hosted international visitors at his home on Lake Martin countless times and traveled to the Philippines in 2004, where the group conducted water quality monitoring workshops.

Mr. Bronson in the Philippines, 2004 conducting a bacteriological monitoring training. Photo credit: Global Water Watch

And on the last day of the year GWW received the sad news of the passing of a wonderful GWW ambassador, Chilean monitor and trainer Juan Vera. The condolence messages came from all Chile…

- Today we are in mourning… our teacher, friend, companion, buddy, co-researcher, traveling friend, our dear village scientist Juan Vera, monitor and trainer of the Global Water Watch program, pillar of Parque para Penco, Park of the Koñintu Lafken Mapu Association, and part of Manzana Verde family, has left this dimension.

- Amid the confusion of losing him on the physical and material plane… we celebrate his life and the pleasure of having had his company… of knowing him in his multiple facets, of knowing his stories as a jupachino, as a librarian, as a mischievous child, as a loving father, husband and brother, as a teacher, as a trainer, as an inveterate joker, as a craftsman, as a master of preserves and other forest contraptions, as a guide, as a hunter, as a facilitator, as a colleague… Juan Vera in his multiple capacities, skills and surprises.

- We had the pleasure of working together and documenting much of his knowledge and his way of understanding and practicing reciprocity with nature from the Mapuche and peasant worldview; and we are certain that he wanted this to continue to be shared and disseminated. That is why we left many of his teachings in the photographs… so that they are sustained here, in the timelessness of this network and that we can turn to him when we need it.

- Thank you, Juan Vera, to you, to the time you dedicated to the network even when the energies were already fading, for being a great father and husband to Emilio and Paola and for all the happiness and deep knowledge of the Penco River basin that you gave us.

- We accompany your journey with love and tenderness, and we thank the family of Parque para Penco, Global Water Watch Chile and International and Rios Protegidos for accompanying your process of transcendence.

- May you continue to be reborn in the queules and in the cycles of the beings of the river that you learned to love as soon as you met them. You will continue to be present in each monitoring and Global Water Watch Chile and the Park for Penco will be your legacy.

- Thank you for giving so much joy to the chachaiyem… for always holding him high as he deserved.

- I am very sorry for your loss. Juan undoubtedly leaves behind a great legacy of love that will live on in you all.

- I had the opportunity to meet him in his stories that he told with emotion and conviction about nature.

- Peñi Juan will always live in the hills of Penco and his spirit will remain in our waters, grateful to have met such a beautiful being, goodbye Lamien Juanito we will always remember you!

- Great Juanito, inspiration, and what a blessing to have this knowledge immortalized forever.

Juan Vera, monitor and trainer of the Global Water Watch program, Penco, Chile.

GWW monitors and volunteers in Chile, Mexico, Peru, the US states of Mississippi and Washington and other places will continue gathering bacteriological, chemical and macroinvertebrate monitoring data on specific waterbodies across their countries. Their goal is to collect and establish baseline data of water quality observations within all possible watersheds to determine if they can provide clean water for the forests, its ecosystems, as well as the public—thereby, get better informed about land management and land use decisions. Let us hope for a peaceful and productive 2025, thank you again GWW friends.

- Photographs by Felipe Zanotti and the Manzana Verde Team

Back to Chile in 2024

Sustainability is our needed destiny, was written on the napkin and paper cup provided by the flight attendant on our flight from Santiago to Concepción. It refreshed in my mind the reason I was visiting Chile one more time. Chile is a little over 2,650 miles long, and that is only 70 miles shorter than the distance from Miami to Seattle. It is also quite narrow with an average 110 miles wide, similar to the width of the state of Florida crossing over Orlando. The one hour and ten minutes flight was smooth with no turbulence, blue sky and most passengers enjoyed the beautiful views of the snowcapped Andes on the left side of the plane and the blue Pacific Ocean on the right. And the text on that cup and napkin reminded me what I am doing as part of Auburn University Water Resources Center, and most of all, made me think about my daily routines, and my personal beliefs, choices and goals in what I have left to live.

Sustainability is a beautiful term. A word that maybe too many people try to use, and often is misused today; but that somehow also reminds me of the word capitalism. Sustainability as well as capitalism are definitely very complex concepts, but giving them more thought, they seem to have a few things in common. A similarity could be the fact that the US culture seems to want the whole world to embrace capitalism, and at the same time that everybody should also embrace sustainability. Sustainability can be seen as a matter of ethics and morality, as capitalism should be, but it is not. Capitalism, as we have it, turns humans into self-interested and self-centric individuals. It causes humans to constantly demand for more and more and there is no end to their wants. Yet, the ecological and social risks of capitalism are real and have reached a dangerous point of no return. It is quite possible that both, capitalism and sustainability, may fail if more and more people lose sight of compassion and limits, of ethics and morals; of the fact that the world’s resources are not infinite, and of the need to accept that at some point, enough should be enough.

The second and third week of October I had the opportunity to take a short vacation to visit, for the third time, the beautiful and marvelous South American country of Chile. Chile is without a doubt a land full of amazing ecosystems but also of much art and plenty of history. I was introduced to Chilean culture in the late 70s, the very first year I started attending the Center for Marine Studies and Aquaculture of the University of San Carlos in Guatemala. One of the faculty members, Dr. Francisco Orellana was Chilean and immersed us in Chilean culture and inspired me to dedicate my life to natural sciences. And through him we started listening to the music of Victor Jara, Violeta Parra, Inti Illimani, Quilapayún, Tito Fernandez, and many more. Chile is the land of many amazing writers, and in the old days we were introduced to poets like Jara and Parra mentioned above, and Gabriela Mistral and Pablo Neruda, both winners of the Nobel Prize of literature. Dr. Orellana conversations also provided more meaning to the Chilean poems we had to memorize in school, which decades later still resound in my mind:

That translates into this: I like you when you are quiet because it is as if you are absent, and you hear me from far away, and my voice does not touch you. I like you when you are quiet because it is as if you are absent. Distant and in pain as if you had died. A word then, a smile is enough, and I am happy, happy that it is not true. An of course there are some words of Neruda that can easily connect with sustainability, like when I change the word “love” for “earth” on this one: “Do not do with earth what a child does with a balloon; when he has it he ignores it, and when he loses it he cries.”

Since our first contact in 2021, GWW partner in Chile, Fundación Manzana Verde (FMV) have been working 24/7 taking community-based watershed stewardship to the next level in many communities in the country. This time, our first journey in Chile took us back to Laja, the city that breathes and lives thanks to La Señoraza lake; in fact they revere it. The two-hour train ride from Concepcion to Laja, along the shores of the Biobio River, is a relaxing and unforgettable adventure. With a few short stops at lovely small towns and with the magnificent Biobio all the time on the right side; the time seems to stand still, and at the same time to pass too fast. Soon our train was crossing the bridge over the Laja River, within sight of the much larger Biobío River, in fact, very close to where the Rio Laja enters the Biobio. It seemed like we had just blinked and suddenly, we were walking from the Laja train station to the Liceo Héroes de la Concepción, in the City of Laja.

A dozen students, a teacher and several community members, certified last year as GWW monitors, have been monitoring at three locations in Laja. They all got reunited again at this local school to attend recertification. Chilean GWW trainers DR, EF, and OC traveled with me to conduct a classroom session with questions and answers about the three types of monitoring; and also to visit La Señoraza lake and the small creek flowing from it, to observe the local monitors conduct every test from the water chemistry kit as well as to practice bacteriological monitoring.

After a delicious lunch all participants moved to the Laja River to practice stream biomonitoring. The river was a little flooded forcing the practice to happen only near the shores and in more shallow waters. Nevertheless, everybody enjoyed observing the macros collected, plus some small fish also caught with the biomonitoring nets. Six new students highly interested in science, participated in all activities and will be certified next year to officially be part of the GWW monitors in Laja and integrate in the ongoing collection of long term citizen monitoring water data.

Friday we got up early to ride to Tomé, the city where GWW-Chile has been holding training sessions and many other environmental education activities. The local municipality has been a model collaborator and sponsor of GWW trainings; including the one in November 2023, when municipality employees and local teachers were encouraged to get certifications in water monitoring. This time the classroom activities were held at the Bellavista School gymnasium, with the participation of almost 50 new monitors. Field practices took place at the Bellavista River, which is a perfect location for accommodating large monitoring workshops for its water quality and biodiverse macroinvertebrate fauna.

Sunday, October 13, 2024 about 30 more monitors from other locations in Chile joined the gathering in what was considered the first annual meeting of GWW-Chile. There were social activities, speeches, delicious food and sharing of numerous monitoring stories.

Usually people do not value what they do not know, and they do not preserve what they do not value. That was a statement said by one of the presenters at the IV Meeting of Protected Areas and Gateway Communities, an event organized among others, by the Protected Rivers Foundation. Gateway communities are all those localities, physically or culturally, close to a protected area. Today about one third of Chile’s surface is protected under some form of land and marine protection. About 200 attendees participated in the event held at La Moneda Palace, a historical building that houses the president of the Republic of Chile and other ministries. FMV Débora Ramírez as part of the Coalition for Protected Rivers working team was recipient of an award for their work. FMV Esteban Flores, spoke about the GWW-Chile initiative to expand participatory community-based, science-based watershed stewardship and water monitoring, as part of a panel. On the second day of the meeting, E. Flores moderated the panel Citizen Science to Protect Water Bodies, where I participated along with D. Ramírez, Juan Vera and Sandra Cortés. Dr. Cortés is a Pontifical Catholic University of Chile professor and president of the Scientific Advisory Committee on Climate Change, recently formed by the Chilean Ministry of Science, Technology, Knowledge and Innovation. She specializes in the study of climate change and its impact on public health.

I was assigned to respond to questions about citizen science, citizen data credibility and validation, and quality assurance-quality control plans. Additional information discussed included how GWW started and highlighting success stories of GWW work in the US, the Philippines, Mexico, Peru and even in the relatively new GWW-Chile. I took the opportunity to remind the participants about what a speaker at the event said the previous day: “Tomorrow Chile can be a model for sustainability”, and I told them today “why wait, we must start today”.

After a few days in Santiago, we traveled to the coastal town of Santo Domingo, Valparaiso province, to conduct an environmental education activity with 24 students and two teachers from the Colegio Pucaiquén. After initial introductions in the classroom, we all went outside to start the activity with a variation of the game Macroinvertebrate Mayhem, which provides a meaningful opportunity to take learning about aquatic invertebrates outdoors, and helps participants to understand how macroinvertebrates are used as bioindicators. Every student was provided a card printed with a macro and information about the feeding habits and pollution tolerance of that macro. GWW categorizes macros in three groups: Group 1, very sensitive to pollution, Group 3 quite tolerant, and Group 2 which tolerate a wider range of conditions. Three participants were assigned the role of “point and nonpoint source pollution” that would enter the narrow area designated as the “river channel” where all macros were living. After three rounds of pollution waves, participants experienced in a very tangible way how the distribution and diversity of macroinvertebrate species was affected over time.

MacroMayhem was a big success, and it was supported with a comprehensive introduction to the nature of macro-invertebrates and their role in assessing water quality. Back inside the classroom the concept of watersheds were introduced with the making of a 3-D map using a piece of fabric, cotton/wool yarn of various colors, and other handy materials and objects. Teachers and students were thrilled when the environmental education activity ended with a demonstration of water testing and the magic of pH testing and acid pollution.

GWW US-based traveler conducted one last activity before departing Chile, visiting the Municipal Natural Preserve (RENAMU for its Spanish name) in the town of Peñaflor, a commune of the Talagante Province in central Chile’s Santiago Metropolitan Region. Peñaflor is about 40 km SW of Santiago, and we demonstrated stream biomonitoring and water chemistry testing in the Mapocho River that runs through the preserve. The Mapocho River was flowing relatively high with a strong sewage smell, which RENAMU leaders said comes from municipal outflows about 7 km upstream. Obviously, very few macroinvertebrates were caught, mostly midges and aquatic worms. Contrastingly, sampling a small tributary flowing into the Mapocho about 20 m upstream from its mouth, yielded an excellent biotic index of 23, with numerous Group 1 (4) and Group 2 (4) macros.

The overnight 4,700-mile trip back to Atlanta was peaceful; I slept most of the way and as the sun was rising I woke up and returned to the normality of the US, greeted by the headline of “3 killed and 8 injured in a mass shooting after a homecoming game in Mississippi”. Another normal day in the self-proclaimed world leading USA. Sometimes it is disheartening to realize that while some of us keep trying to help the planet through citizen science and environmental education, it is hard to hide that unfortunately many others have their priorities on different issues. As part of the AUWRC we will just continue doing as much as we can and want, bridging the big gap that exists between the way nature works and the way people think and act. Every day every one of us should reflect on our common sense of goodness and rightness, of compassion, ethics and morals, in our relationships with each other and our relationships with the earth.

GWW-Chile is rapidly growing and the interest and commitment of each new monitor is inspiring; there are now almost 250 certified monitors, regularly testing in almost 100 sites distributed from San Pedro de Atacama to Futaleufú. And the interest for GWW monitoring has reached as far south as Puerto Williams, basically at the tip of the American continent. ===============================

Amigos del Pixquiac 200 Monitoring Events

Last year, on July 30th of 2023, our partners in Mexico, Amigos del Pixquiac (Friends of the Pixquiac River), joined for their 200th time to conduct one more Global Water Watch monitoring event at their beloved river. Accomplishing 200 monitoring events was an unthinkable milestone for Eduardo Aranda, who is one of the leaders of Amigos del Pixquiac and probably the GWW-Mexico monitor with the most records ever collected. I asked Eduardo to share with us some of his thoughts about reaching this milestone, and share memories and some of the many unforgettable moments he has lived while monitoring the Río Pixquiac. This is a loose translation of what Eduardo had to say about that event and his time monitoring with Amigos del Pixquiac:

It is a bit difficult for me to review and summarize the 200 water-monitoring events of the Pixquiac River in these 18 years that have passed since 2005. Because of the memories, the historical conditions, the personal circumstances, social problems, opportunities and even different emotions are certainly intermingled.

What I can say is that at that time, in the year 2005, a group of residents of Zoncuantla, residents of the Pixquiac River watershed, had the concern of being able to know or analyze the water quality of the river. The only alternative that we could recognize was to carry a sample of water to a private laboratory and request them to do some analysis, but without really knowing what tests should be or even how much it would cost us to do it, much less being able to obtain an interpretation when we had the results in our hands.

Eduardo Aranda (left) and a group of Amigos del Pixquiac while conducting the 200th water monitoring event at three sites in their river on July 2023.

It was in that August of 2005 that we attended an event, with the curiosity to listen to a series of conferences that were conducted at the Institute of Ecology in the Clavijero Botanical Garden in Xalapa. There, among other topics, we were able to listen to interesting talks by colleagues from the University of Auburn, in Alabama USA, with the special charisma of Dr. Bill Deutsch and Sergio Ruiz Cordova (Guatemalan).

During those conferences, we were presented with a novel and magnificent opportunity with which, ourselves as a community, could carry out not only one isolated analysis of the water, but many periodic samplings of our river and also be able to interpret and understand the results, and draw our own conclusions and care recommendations for our river. In addition to everything, the next day we began participating in a series of training sessions to certify us as “GWW Monitors”, in which we were lucky enough to conduct the fieldwork in our Pixquiac River…!

Bill Deutsch and Sergio RuizCórdova interpreting bacteria monitoring results at the first GWW training in Mexico in 2005, Eduardo Aranda taking photos.

That was the beginning, and our enthusiasm was capped with the generous donation of the Physical-Chemical Monitoring Kit, with which we already had everything we needed to begin monitoring, and that is how we started…!

Beautiful view of the river during a water monitoring event of the Amigos del Pixquiac.

Our initial objective as Monitors was to be able to recognize and understand the quality of the water in the Pixquiac River when arriving at, and when leaving our community in Zoncuantla. A few months later, we were invited to visit Auburn, Alabama in the United States to learn other monitoring techniques and to meet other groups that had been carrying out these activities there for a long time. The trip opened our eyes to new opportunities, not only to continue learning but also to be able to share what we knew and teach to others in our country, as we became GWW Trainers.

After our return from the GWW headquarters in Auburn, we began conducting visits and trainings in other states: Chiapas, the State of Mexico, Oaxaca and other places. Those interactions allowed us to broaden our understanding of rivers, their similarities and differences, but above all, to meet many wonderful people with the same desire to contribute their time and effort to take care of our rivers.

I want to acknowledge the always kind and generous presence and unconditional support of Bill, Sergio, Eric Reutebuch, Mona Dominguez and many others in Auburn, as well as the companionship, support and determination of our colleagues in Xalapa. Many of whom not only have accompanied us to countless monitoring events of the three sites on the Pixquiac River, but together we saw ourselves with the opportunity and responsibility of starting Global Water Watch Mexico and thus being able to expand our reach and our influence everywhere we were asked to go.

I want to highlight that in all these 18 years of monitoring the Pixquiac River, we have had the opportunity to see the river in many, if not all of its presentations. From observing imposing and dangerous floods, moments of calm and wonderful beauty, to witness moments that we did not expect to see, with points and events of high contamination, to even periods and sections of the river, with the streambed completely dry, without a drop of water… In these 18 years, as a community we have experienced population growth problems, environmental threats, pollution attempts, as well as opportunities to enjoy a beautiful, healthy, and magnificent river that has given us beauty, peace, and gratitude. Without a doubt I can say that these 18 years have been a wonderful learning experience, of coexistence and personal growth, recommended for everyone and at any stage of our lives…!

A sad view of the Pixquiac River during an unusual period of drought in 2023 .

This 200th monitoring event of our Amigos del Pixquiac was another highlight and testimony of the expansion of global environmental awareness and literacy through the Global Water Watch’s promotion of community-based, science-based watershed stewardship and water monitoring. Of course, there was a celebration with great food, fruits and drinks, as well as great conversation and camaraderie among the new and the seasoned Amigos del Pixquiac. In the end, there was a light of optimism in all the water monitors from Zoncuantla and Xalapa; there was a consensus that they are doing something good to keep their river alive and in good health. And that of course reminds me the last part of the AU WRC mission that proclaims to empower private citizens to become active stewards of water resources. GWW would like to commend the commitment of these exceptional water stewards, as very few have the dedication to achieve such an impressive milestone.

GWW Mexico on World Water Day

by: Miriam Guadalupe Ramos Escobedo, GWW Mexico Director

It has been a long time since 2005, when GWW Program Director William Deutsch gave us an illusion. It sounded so clear, so logical that it seemed to be a sure road, but his words should have also been a warning with what he said.

¨The good thing of starting GWW México from scratch is that nothing has been done, so you can make it whatever you dream; the bad thing is that NOTHING has been done¨.

Well, after 18 years of trying to spread community-based, science-based water-monitoring (CBWM) in México, I am not sure if we had a dream. We thought it was important for sure, we thought it was needed.

That is how we began our CBWM journey in the Mexican state of Veracruz. Trying to learn all the work from the actual water monitoring, to the work behind the scenes. What is done before and after the workshops, the follow up, seeking for funds, engaging people, linking with groups, etc. In addition, something more important, trying to persuade the authorities that this participatory monitoring is a valuable tool in the strategy to ensure healthy water, healthy streams, rivers, lakes and beaches.

The GWW Mexico journey has been a long one considering that our conditions in Mexico are quite different from the conditions in Alabama, therefore our groups usually do not survive without a funded project that can provide the resources to sustain the monitoring. Many people in Mexico are new to the culture of volunteering, mostly in such a systematic way as needed for long term water monitoring. In addition, some people want to see fast results, after 3 to 6 months if nothing has changed they start to lose interest.

Nevertheless, there is still a great need for information on water, and somehow, we keep going.

We have found people that just want to know if their water is safe, or why they get rashes when they take a shower. Other people want to have data to make a statement with the government. And a few others want to know why they cannot find wildlife there anymore, animals and plants that used to populate their streams.

Each group is a story and a journey, each group represents a different challenge. But even if most of our groups cannot last long term, they go thru a process that helps them see their water resources and freshwater ecosystems with a different perspective. So this week, the week of World Water Day, several thing are going on with our friends.

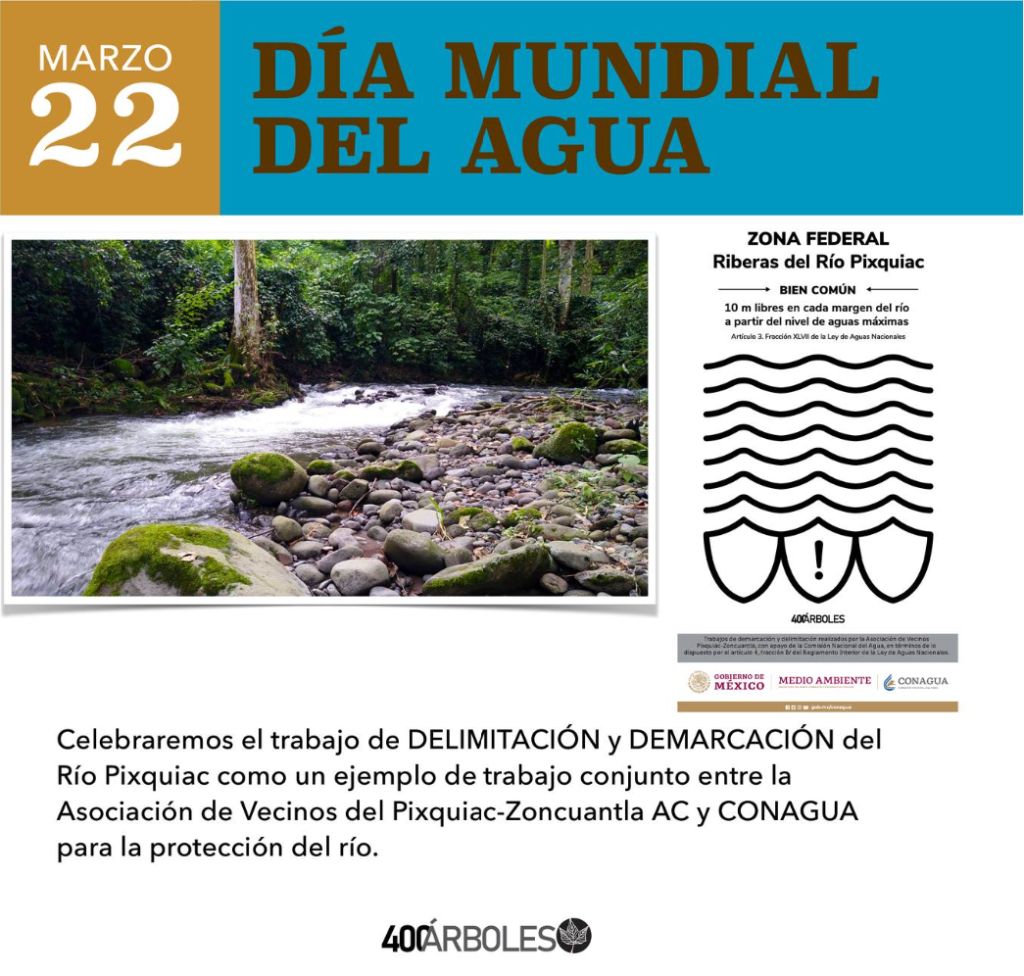

In our beloved state of Veracruz the first GWW water monitoring group that was established in Mexico, the Amigos del Pixquiac, is still quite active. They collaborate with the organization Vecinos del Pixquiac Zoncuantla and have been pursuing a bureaucratic procedure that has no precedent in Mexico. After almost six years of conversations, they finally are obtaining their Pixquiac River riparian zone officially delimited in collaboration with CONAGUA, the national water authority.

Something else is also happening about 700 km west of Veracruz, on the banks of the southern part of the Pátzcuaro Lake, in the city of Huecorio in the state of Michoacán. There, members of the group CECyTEM are presenting the results of their GWW community-based water monitoring to the Asamblea Purépecha. The Purépecha are one of the many ethnic groups in México, and they subsist greatly from fishing as they mainly live around the Pátzcuaro and Cuitzeo lakes.

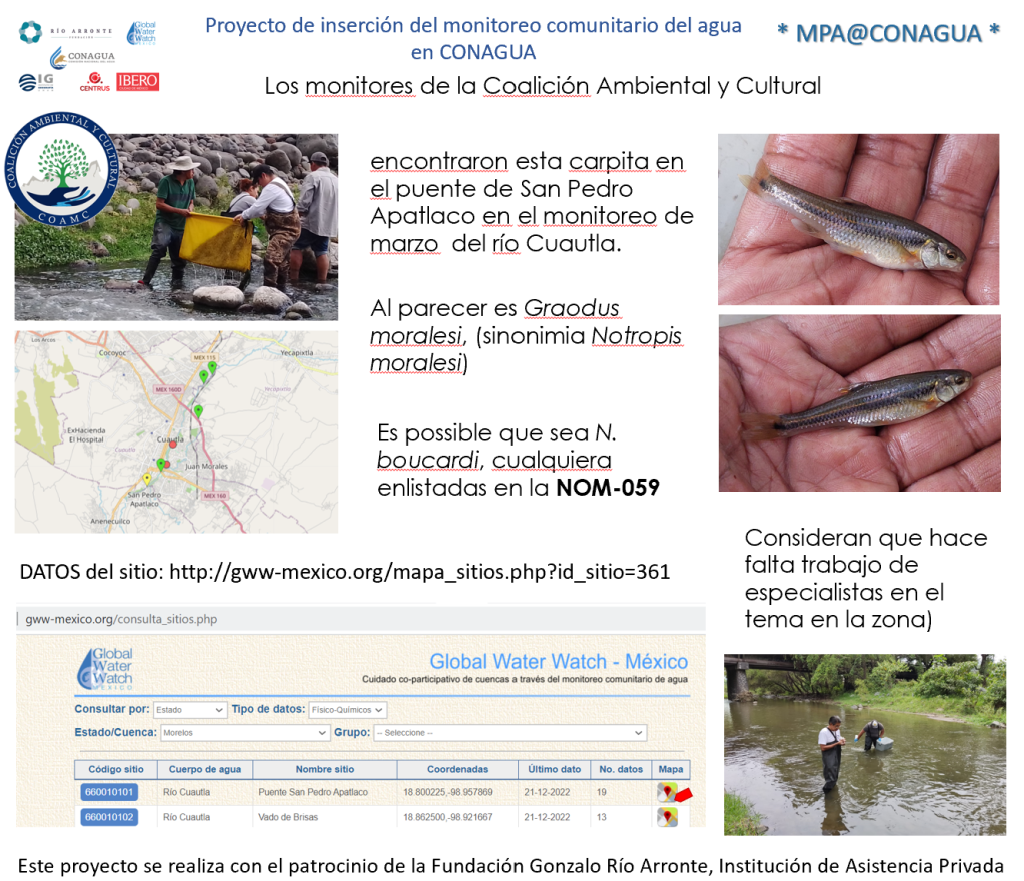

South of Mexico City, in the state of Morelos, GWW monitors in Cuautla are also presenting their results from water quality and biodiversity at the Fifth Festival of the Río Cuautla. This group actually found an endangered fish while conducting their water monitoring this month!

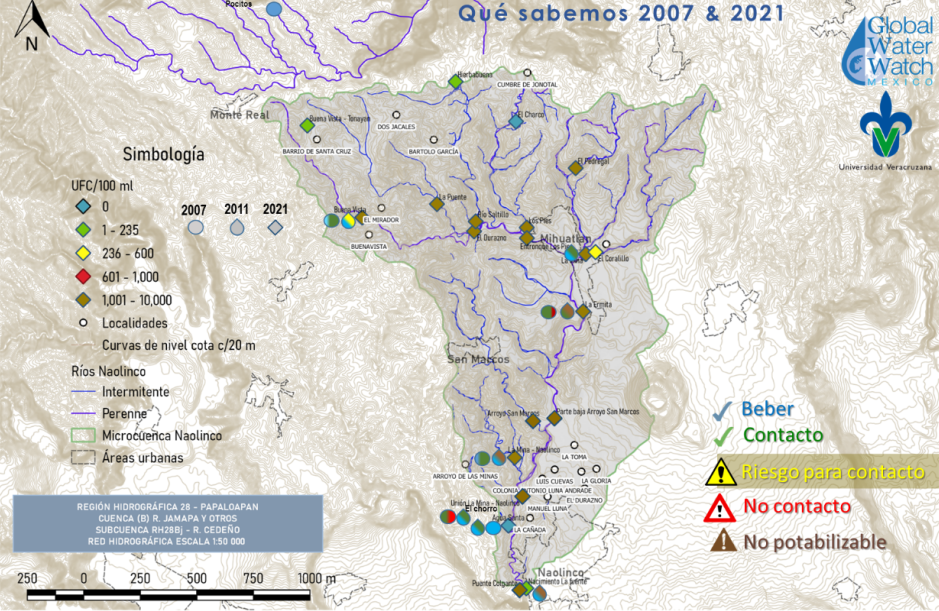

Getting back to our state of Veracruz, in the city of Naolinco, the GWW group is summarizing water-monitoring data gathered from 2007 to 2021 with the participation of the community. The community also collaborated in the mitigation of wastewater pollution with the construction of an artificial wetland to direct and treat their sewage instead of discharging it directly into the streams.

GWW Mexico collaboration and accomplishments go beyond Veracruz and all of Mexico. Conversations for more than a year with the Fundación Manzana Verde, a group in the Biobío region in Chile, led to a visit last year from them to Veracruz. During their visit, they learn from the GWW Mexican experience, meeting local monitors, observing and practicing water monitoring. After returning to Chile, a big Chilean group got certified as GWW water monitors in September 2022 and started monitoring. Recently we have heard that they are in conversations with the regional government to receive funding and have the opportunity to expand and consolidate the CBWM over there.

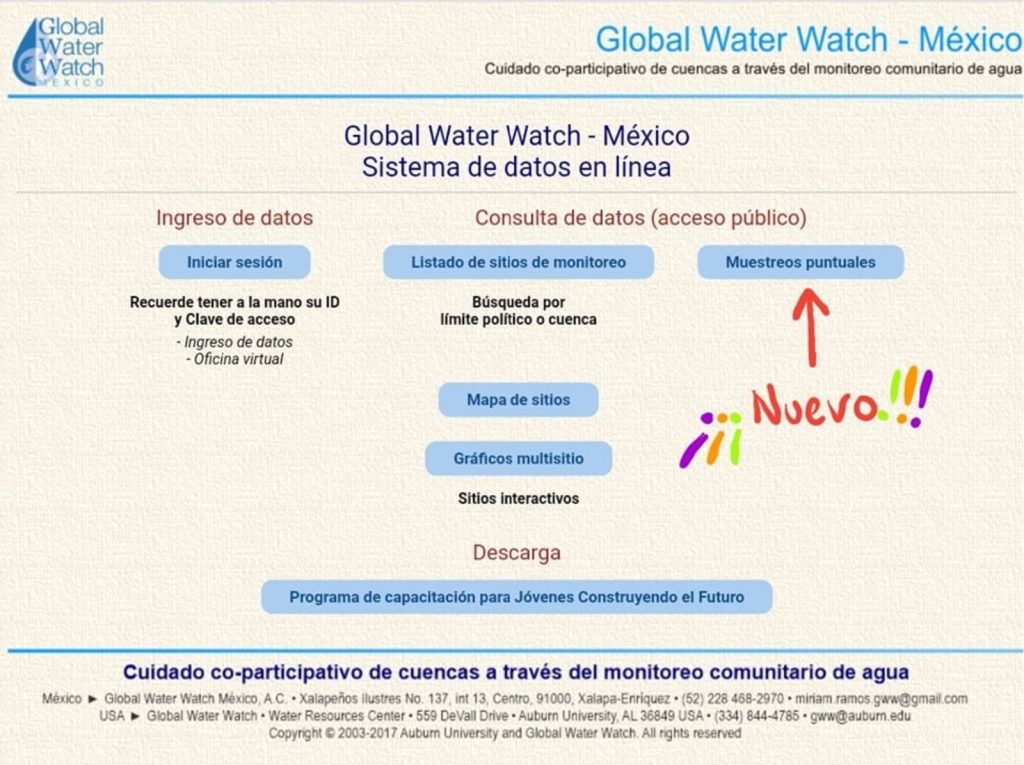

So, it has been a long journey, full of bumps, falls, lots of work and with a blurry road ahead sometimes. However, after 18 years, we can celebrate our accomplishments. The GWW Mexico database holds almost 14,000 water monitoring data records: 5,487 bacteriological records, 6,549 water chemistry records, 257 biomonitoring records, 868 stream flow records and 801 total suspended solids records. In addition, this World Water Day, we added a new feature in our water data webpage to reflect the energy of the people that want to get things moving related to water: a button to show data obtained by punctual sampling, not necessarily systematic monitoring, because we are in so much need of information that every drop counts!

Visit us at http://gww-mexico.org/

HAPPY WORLD WATER DAY!!!