This past Thanksgiving Day I was in Peru’s Highlands taking a short vacation, as some would say. These highlands are so beautiful and breathtaking that I could stay there forever, admiring them. The mountains are high, the valleys immense, all above the tree line (approximately 3,900 meters or 12,800 ft above sea level) and covered with grasses. Most communities survive on small self-sustained agriculture, few cows and large herds of alpaca, llamas and sheep.

I returned to Perú after about 10 years, on behalf of Global Water Watch (GWW), the larger umbrella of citizen water monitoring groups based in the Auburn University Water Resources Center (AU-WRC) in the US. The trip was possible after a couple of years of conversations and a result of a strong collaboration of the NGO Derechos Humanos y Medio Ambiente ꟷDHUMA (Human Rights and Environment) which is based in Puno, Peru and is developing a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to be signed by DHUMA and GWW. The purpose of the MOU is to coordinate the fostering of Community-Based, Science-Based Watershed Stewardship (CBWS), and citizen-based water monitoring in the Peruvian Departments of Puno, Cuzco, and beyond. The main goal of this trip was to conduct CBWS workshops with GWW certifications in bacteriological monitoring, stream biomonitoring, and water chemistry monitoring, and to coordinate the expansion of GWW CBWS activities in Peru with DHUMA.

The GWW activities during this trip started, with the collaboration of the NGO Human rights without Borders, in the city of Espinar, in the Cuzco region, where twenty-one community members were certified as water chemistry monitors. We conducted monitoring practices on the Apurimac River, the water source for several of the communities. Afterwards, we shared and discussed the water chemistry monitoring results.

The next stop for GWW activities was in the city of Puno, where 35 community members, some of them already environmental water watchers and monitors, from Yacango, Coata and Caracoto, participated on November 13 and 14 in the GWW sessions on bacteriological monitoring, physical and chemical monitoring, and stream biomonitoring using macroinvertebrates. The new GWW monitors including students, teachers and community members believe that this certification will improve their abilities to monitor. They feel that participatory community environmental surveillance and water monitoring are valuable tools for self-advocacy.

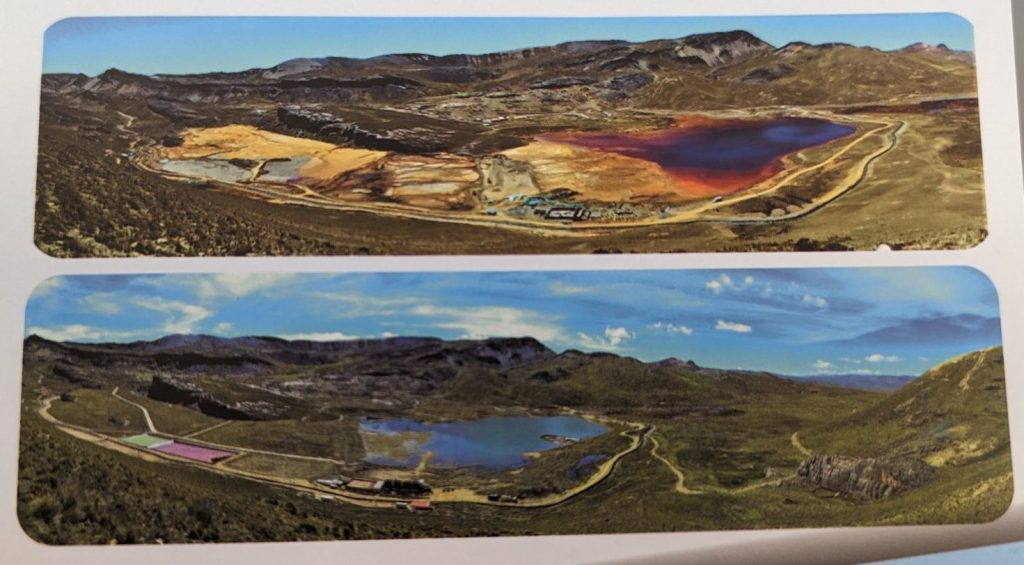

A highlight of the trip was a visit to the Condoraque watershed; where I had been back in 2009, when GWW traveled to Puno to conduct the first water monitoring workshops, which included some community members from Condoraque. Since the late 1970s, the communities along the Condoraque River had been seeing their river turn from a healthy river to a yellowish river carrying the outflow of a mining operation at the top of the mountain. Villagers referred to the Condoraque River as “burning waters” because of the toxic waste coming from the mine upstream, which made the river untouchable. The original mining company left in the 1990s, and did no type of reclamation. In 2010, the Condoraque case concerns were presented to the United Nations in New York. As a result, the second company that bought the mining rights of the area agreed to the condition that it would repair the environmental damage caused by the first mine.

This time, the view of the Condoraque River was different. A consultant group, Cumbres del Sur, has been working on remediating the mining damage and their efforts have been effective so far. A water treatment plant was installed and is treating the water still flowing from the mine, right next to the Choquene Lagoon, that held most of the contaminated effluents and has been dredged, and flora and fauna can be seen back in the water and shores. Downstream, on the river, I picked up some rocks from the channel and found macroinvertebrates and saw some fish.

A group of Condoraque residents came along to the visit and guided tour of the treatment plant by the Choquene Lagoon; they are happy that the river is returning to life, yet they still see the need to continue the remediation work downstream. Although this looks and sounds like a win for nature and the indigenous communities in Condoraque, it is only one of hundreds of rivers and watersheds in Peru, that are in the same situation Condoraque was 10 years ago. Only two days before we had visited the Llallimayo River, and the view there is very sad.

We got up at 3 am to reach the Jatun Ayllu River up in the mountain near the Aruntani S.A.C. mine. The trip from Puno takes almost 5 hours, so after a while we stopped for a big breakfast in the city of Ayaviri, which lays on the north side of the river. After about one hour from Puno, the road more or less follows the Llallimayo riverbanks for many miles. Both the Condoraque and Llallimayo rivers flow into Lake Titicaca carrying a load of heavy metals. The lake that straddles the border of Bolivia and Peru and was once revered, has become a dumping site for trash, and the fish from the lake that is a staple in many diets in the region, contain dangerous levels of cadmium, lead, mercury, and other heavy metals. Recent blood and urine tests from residents, including children ages 4-14, along the Coata River near Juliaca revealed high levels of arsenic and mercury.

As stream enthusiasts usually do, at the confluence of the Jatun Ayllu River with a clean tributary flowing from an undisturbed mountain, I got near the water and picked up rocks from the channels, looking for life. The rocks on the clean creek were covered with macroinvertebrates, mayflies, amphipods and other; while the rocks from the Jatun Ayllu were covered with a thick layer of yellowish sediment containing who knows what. For over ten years, that has been the life of the residents downstream from the mine, a yellow river that sometimes turns orange and other times green. They have condemned the pollution of the tributaries of these basins, the death and malformation of their alpacas, sheep and cattle and the disappearance of cultivation pastures.

The gold mining industry is one of the most destructive industries and has a devastating impact on ecosystems worldwide. I never had a gold ring, but realize that for many it is quite important. Yet, next time you buy a gold ring consider the following: Earthworks estimates that to produce enough raw gold to make a single ring, 20 tons of rock and soil are dislodged and discarded, producing waste that carries mercury and cyanide, which are used to extract the gold from the rock. Gold mining may be done with less environmental impact, and as we saw in Condoraque, some of the damage can be prevented.

This GWW trip to Peru was another step to expand global environmental awareness and literacy through community-based, science-based watershed stewardship and water monitoring. After the trainings I could see a little light of hope in the new water monitors from those communities; and that made me recall the last part of the AU WRC mission that says empower private citizens to become active stewards of water resources.